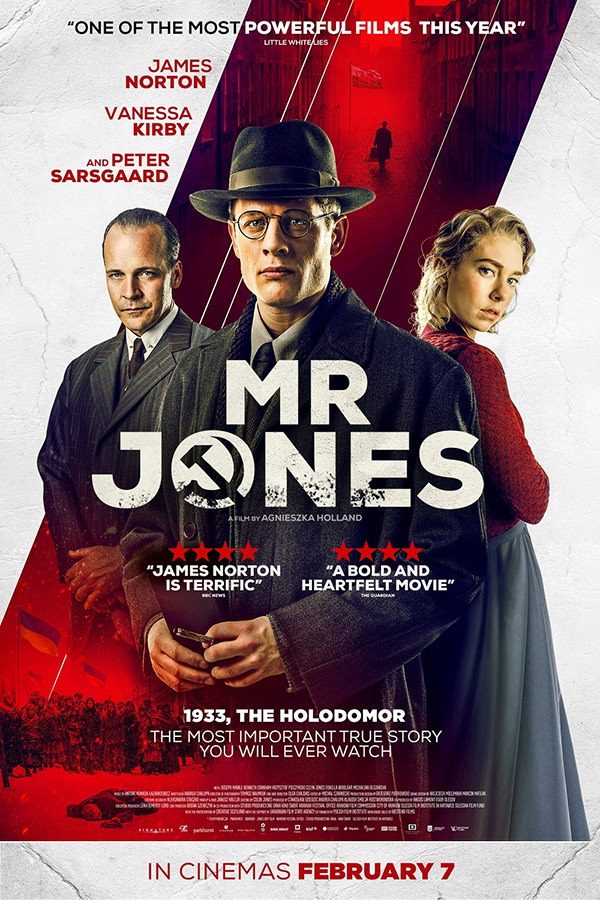

Mr. Jones

Directed by Agnieszka Holland (2019) ***

The Polish film director and writer Agnieszka Holland always makes films worth seeing due to her unique perspectives (she was arrested in 1968 in Czechoslovakia during the Prague Spring and worked/studied under film director Andrzej Wajda). One of her most recent films is also one of her most timely and relevant: Mr. Jones, a look back at reporter Gareth Jones’ 1930s exposé of the Holodomor, Stalin’s man-made famine in Ukraine, a genocidal nightmare which killed millions of people. The grain-harvesting program was, at least partly, an attempt to squelch an independence movement in Ukraine. Nearly a century later, Russia is still unhesitant to kill Ukranian citizens for the same reasons.

The Polish film director and writer Agnieszka Holland always makes films worth seeing due to her unique perspectives (she was arrested in 1968 in Czechoslovakia during the Prague Spring and worked/studied under film director Andrzej Wajda). One of her most recent films is also one of her most timely and relevant: Mr. Jones, a look back at reporter Gareth Jones’ 1930s exposé of the Holodomor, Stalin’s man-made famine in Ukraine, a genocidal nightmare which killed millions of people. The grain-harvesting program was, at least partly, an attempt to squelch an independence movement in Ukraine. Nearly a century later, Russia is still unhesitant to kill Ukranian citizens for the same reasons.

Mr. Jones begins with Gareth Jones, played in the film by James Norton, being scoffed at by British elite for his warnings about the dangers of Nazism (he interviewed Adolf Hitler in 1933 on a trip to Frankfort with Joseph Goebbels). On a third visit to the Soviet Union (the film portrays him as wanting an interview with Stalin, but the real Jones may not have been that naive) he intends to investigate the mechanisms of the Soviet’s improbable industrial progress. A journalist colleague of his working there on a similar story is murdered before he arrives. Jones there meets with New York Times journalist and Pulitzer Prize winner Walter Duranty (played with unctuous charm and menace by Peter Sarsgaard) and his assistant, Ada Brooks (Vanessa Kirby). Duranty had been bought and corrupted by the Soviet regime and his rosy depictions of Soviet life (and denials of starvation) spread falsehoods to the Western press for decades; the Pulitzer committee, to this day, has refused to revoke Duranty’s award.

On a train trip to Ukraine, Jones escapes his Soviet bureaucratic handler and sets out on his own, keeping notes on what he witnesses, a harrowing journey. This middle section of the film is the real essence of the story, and it may seem unbelievable that Jones was able to travel and survive such distances without being arrested or shot — were it not for the fact that the landscape is so vast, and the reach of Stalin’s operatives so random and so desperate to hurriedly ship harvested wheat back to the motherland. Jones’ reporting, published in The Manchester Guardian, and the then-reputable New York Post, told of strewn dead bodies, houses of dead occupants, cannibalism, and starving adults and children.

On a train trip to Ukraine, Jones escapes his Soviet bureaucratic handler and sets out on his own, keeping notes on what he witnesses, a harrowing journey. This middle section of the film is the real essence of the story, and it may seem unbelievable that Jones was able to travel and survive such distances without being arrested or shot — were it not for the fact that the landscape is so vast, and the reach of Stalin’s operatives so random and so desperate to hurriedly ship harvested wheat back to the motherland. Jones’ reporting, published in The Manchester Guardian, and the then-reputable New York Post, told of strewn dead bodies, houses of dead occupants, cannibalism, and starving adults and children.

Although Jones was not the only Western journalist reporting on the Holodomor (Malcolm Muggeridge, whose character makes an appearance in the film, also wrote reported for The Manchester Guardian), Jones’ reporting was, at the time, looked at by many with incredulousness and Duranty, of course, denounced it as propaganda. Jones was murdered two years later, most likely by a Soviet NKVD agent.

First-time screenplay writer Andrea Chalupa frames the film with a sequence of George Orwell writing Animal Farm (Mr. Jones was, ironically, the name of the alcoholic farmer who first prompted animal rebellion in the novella) and while Orwell was fervently anti-communist, his appearance in the film (in which he also meets Gareth Jones) seems superfluous and distracting.  A surreptitious stealing by Jones into a William Randolph Hearst estate, in order to talk to him, is a late bid for suspense, although Heart did publish and distribute Jones’ last three articles on the Soviet Union.

A surreptitious stealing by Jones into a William Randolph Hearst estate, in order to talk to him, is a late bid for suspense, although Heart did publish and distribute Jones’ last three articles on the Soviet Union.

Holland’s film, though, is to be credited for what it does get right, beginning with the era and locales, the cold, crisp winter weather of central Moscow, the lurking and spying distrust of foreign correspondents, the dark ornate publisher’s offices, the Stalin posters promising bounties of food, the decadent, state-sanctioned drug and alcohol-infused parties for the elite, evoking the atmosphere of Weimar-era Germany. The Ukranian landscapes, barren with white snow and downcast skies are a fitting environment for lonely tragedy. James Norton, also appearing this year in Bob Marley: One Love, gives his character the gravitas the story requires, and all involved had the good sense to not crowbar a romance story into Jones and Ada Brooks’ relationship. Mr. Jones may not be great art, but it is a great story and, presciently, speaks to today’s headlines.

—Michael R. Neno, 2024 April 15