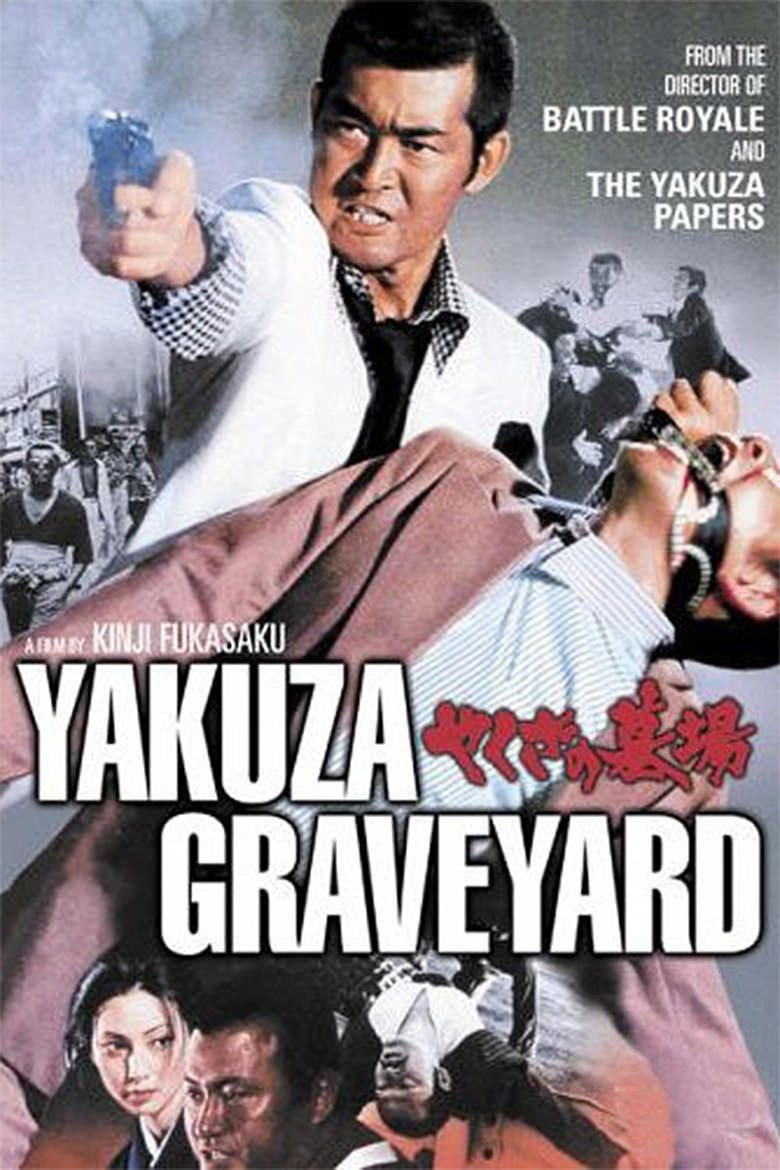

Yakuza Graveyard

Directed by Kinji Fukasaku (1976) ***

Although 1960s films were the first to delve into explicit violence, in works like The Wild Bunch (1969), Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Night of the Living Dead (1968), ’70s cinema brought it to fruition. The Japanese Yakuza (or, gokudo) genre took full advantage of the new freedom; Kinji Fukasaku’s Yakuza Graveyard is like a ’70s Martin Scorsese film on speed. It’s brash and bold, almost feverish, and makes no excuses.

Although 1960s films were the first to delve into explicit violence, in works like The Wild Bunch (1969), Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Night of the Living Dead (1968), ’70s cinema brought it to fruition. The Japanese Yakuza (or, gokudo) genre took full advantage of the new freedom; Kinji Fukasaku’s Yakuza Graveyard is like a ’70s Martin Scorsese film on speed. It’s brash and bold, almost feverish, and makes no excuses.

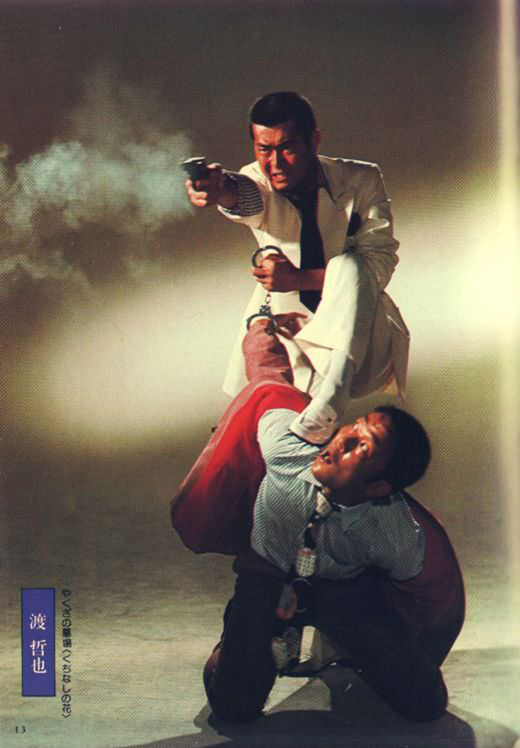

Graveyard is the labyrinthine tale of a corrupt cop in a corrupt system. It’s a tale so bleak there’s barely any difference between cops and mobsters. Tetsuya Watari plays the cynical and restless Detective Kuroiwa, who befriends a Yakuza boss and falls in love with the wife (Meiko Kaji) of another jailed crime boss. In one typical scene, Kuroiwa is grooving to loud American rock music in his apartment when a cop knocks on his door as neighbors are complaining. Kuroiwa promptly punches the cop in the jaw!

An opening scene demonstrates the film’s audacious spirit. After stealing from a pachinko parlor run by the crime family that he eventually hooks up with, Kuroiwa, working undercover, is beaten and humiliated by several of the family’s young hoodlums. He then turns a corner and changes his clothes and disguise (while the camera turns sideways, and the movie title is splashed across the screen). Following the hoodlums and their delinquent itinerary, Kuroiwa confronts them, chases them, beats them to a pulp and arrests them, like a rogue Douglas Fairbanks. This is shot with a handheld camera with startling urgency; Fukasaku directs the film as if his life depended on it.  The colors are bright, the framing close in on sweaty faces and bloody knuckles. Freeze frames are frequently used. It’s a story of street warfare and the directing matches the story’s grittiness.

The colors are bright, the framing close in on sweaty faces and bloody knuckles. Freeze frames are frequently used. It’s a story of street warfare and the directing matches the story’s grittiness.

If you can keep up with all the complex, schematic connections between the rival mobs and police corruption, I tip my hat to you. It’s easy to understand the basic thrust of the plot, though, as Kuroiwa holds to his own sense of honor and refuses to be micromanaged by any competing force, not least of which is the police department.

Yakuza Graveyard doesn’t have the same ambitious artistry of American crime film directors of the era such as Francis Ford Coppola, Scorsese, or William Friedkin. Graveyard’s crime families aren’t the plush, quiet, romanticized sort seen in the Godfather movies. These are loose, street-smart organizations, low to the ground.  In Graveyard, it’s as if the post-WWII Japan seen in early Akira Kurosawa films still continues, with lawlessness and corruption entrenched. And yet, the film finds moments of poignancy, such as when Kuroiwa takes one of two crooks he’s “hired” to see their caustic, weary, salacious mother working in a bar. It’s so personal you nearly feel you shouldn’t be watching it.

In Graveyard, it’s as if the post-WWII Japan seen in early Akira Kurosawa films still continues, with lawlessness and corruption entrenched. And yet, the film finds moments of poignancy, such as when Kuroiwa takes one of two crooks he’s “hired” to see their caustic, weary, salacious mother working in a bar. It’s so personal you nearly feel you shouldn’t be watching it.

Kinji Fukasaku had a long and varied career. After starting in the early ’60s working with the great Sonny Chiba (actor, singer, film producer, film director and martial artist), Fukasaku directed a succession of crime films in the late ’60s, a series of Yakuza films in the ’70s, and directed the Japanese portion of 20th Century Fox’s 1970 Tora! Tora! Tora!. As if that weren’t enough, he’s known for his many science fiction films (The Green Slime, 1968, Message from Space, 1978, Virus, 1980). To younger audiences he’s most famous for directing the notorious Battle Royale (2000), without which Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games series wouldn’t exist.

The Kino DVD features the original trailers for Yakuza Graveyard and Fukasaku’s 1975 Cops vs. Thugs, which looks to be another gun-blasting, two-fisted epic.

—Michael R. Neno, 2017 April 7