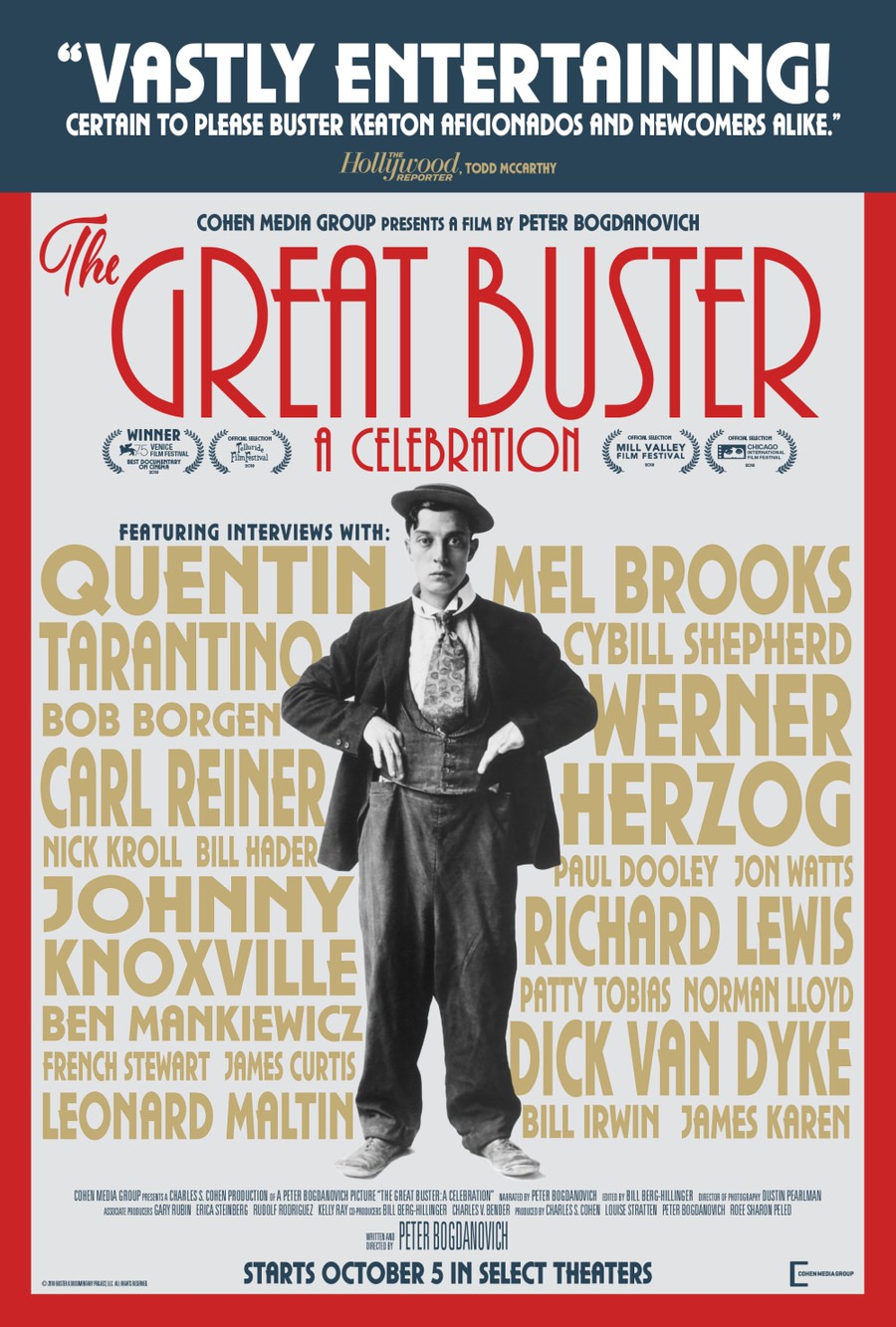

The Great Buster: A Celebration

Directed by Peter Bogdanovich (2018) ***

Buster Keaton was one of the funniest, most inventive and influential comedians and filmmakers in history. And yet: how many Buster Keaton documentaries do we need? Historian Kevin Brownlow’s nearly three-hour Buster Keaton: A Hard Act to Follow (1987) was comprehensive but has never been released on DVD in the United States. Director Peter Bogdanovich, who also has a keen appreciation of the master comedian, covers much of the same territory, 31 years later, in The Great Buster: A Celebration. Not much new has been discovered about Keaton’s art since then, but a more easily accessible presentation of his life could possibly reach a larger audience.

Buster Keaton was one of the funniest, most inventive and influential comedians and filmmakers in history. And yet: how many Buster Keaton documentaries do we need? Historian Kevin Brownlow’s nearly three-hour Buster Keaton: A Hard Act to Follow (1987) was comprehensive but has never been released on DVD in the United States. Director Peter Bogdanovich, who also has a keen appreciation of the master comedian, covers much of the same territory, 31 years later, in The Great Buster: A Celebration. Not much new has been discovered about Keaton’s art since then, but a more easily accessible presentation of his life could possibly reach a larger audience.

That remarkable life has been dissected so often, in a multitude of biographies, documentaries and podcasts that I won’t rehash it here. It’s enough to say Keaton was the proverbial artist ground up and spat out by the Hollywood sausage factory (though he was in good company; a myriad of others were equally used and discharged, among them F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, Keaton’s comrade Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, and even D.W. Griffith). Keaton is known for the decade, the ’20s, in which he made one gloriously hilarious short and feature film after another, all independently created on the fly by Keaton and his hand-picked associates, in his own production unit. The films are by turns surreal, suspenseful, endearing and visually inventive, carried by Keaton’s dry wit and physical dexterity.

These were films made leisurely, by trial and error, under the direction of no one but Keaton himself. (His The General, Bogdanovich points out, is considered by the American Film Institute as the 18th greatest film of all time). When Keaton’s contract was sold to MGM (coincidentally due to the financial failure of The General, which received poor reviews at the time), he became an expendable cog in their decidedly unfunny corporate apparatus; MGM was notorious for not allowing comedians artistic freedom and for micromanaging. Keaton was put into one unfunny film after another, stripped of his ability to create stories and situations, forced to team, water and oil-like, with the very verbal Jimmy Durante, made to play a loser character degradingly called Elmer. The films are, put bluntly, sad and embarrassing.

These were films made leisurely, by trial and error, under the direction of no one but Keaton himself. (His The General, Bogdanovich points out, is considered by the American Film Institute as the 18th greatest film of all time). When Keaton’s contract was sold to MGM (coincidentally due to the financial failure of The General, which received poor reviews at the time), he became an expendable cog in their decidedly unfunny corporate apparatus; MGM was notorious for not allowing comedians artistic freedom and for micromanaging. Keaton was put into one unfunny film after another, stripped of his ability to create stories and situations, forced to team, water and oil-like, with the very verbal Jimmy Durante, made to play a loser character degradingly called Elmer. The films are, put bluntly, sad and embarrassing.

Keaton’s personal life began reflecting his maddening circumstances; he drank more, and then to excess. His wife, Natalie Talmadge, left him, taking their two sons. MGM fired Keaton. The rest of his career was a long, slow, upward climb, though appreciation for his work and talents was rising when he passed away in the late ’60s.

What does Bogdanovich bring to the screen we haven’t already seen from Keaton? There’s not much —some obscure TV commercials, a small, private segment of Keaton and his wife, Louise, snippets from The Scribe (1966). Most of the new footage are interviews with those who knew, respected or learned from his work: Dick Van Dyke (who read Keaton’s eulogy at the funeral), actors Richard Lewis and Cybill Shepherd, Carl Reiner, Mel Brooks, and Quentin Tarantino. Keaton’s appeal to a broad spectrum of disciplines is revealed when director Werner Herzog is interviewed in the same film as Johnny (Jackass) Knoxville.  Jon Watts, the actor behind the mask in Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017), talks of studying Keaton for body language.

Jon Watts, the actor behind the mask in Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017), talks of studying Keaton for body language.

Bogdanovich tries a different angle with The Great Buster than most documentaries; instead of a straightforward narrative, he details Keaton’s early life up to the beginning of his feature film career, describes his many later projects and appearances, and then, in the third act, concentrates on that great decade of masterpieces. It’s here I have a struggle with the way Keaton’s films are covered in documentaries (the same trepidation is true of Brownlow’s doc). Distilling Keaton’s best “bits” into a montage of scenes from various films cheapens the films and the scenes, I believe — one of the reasons I cringe when I see similar Keaton montages in Twitter memes and videos on Facebook, YouTube and TikTok. The scenes are taken out of context. They were and are parts of stories and Keaton, no doubt, would have greatly preferred his work to be experienced as stories, not edited into “greatest hits” conglomerations.

Those who haven’t seen Keaton’s films do themselves a disservice if they don’t watch the films themselves. And this leads to an irony; the only viewers likely to watch a Buster Keaton documentary are those likely to have already seen the films, and they don’t need to be “sold” on Keaton. So, the montages of scenes designed to convey the master’s inventiveness are preaching to the already converted, and those watching the documentary having not seen Keaton’s films are experiencing the art in a way unintended by their creator.

Those who haven’t seen Keaton’s films do themselves a disservice if they don’t watch the films themselves. And this leads to an irony; the only viewers likely to watch a Buster Keaton documentary are those likely to have already seen the films, and they don’t need to be “sold” on Keaton. So, the montages of scenes designed to convey the master’s inventiveness are preaching to the already converted, and those watching the documentary having not seen Keaton’s films are experiencing the art in a way unintended by their creator.

For those viewers who haven’t seen Seven Chances, Steamboat Bill, Jr., College, Battling Butler, etc. I say treat yourself and watch them instead of this documentary. If you’ve already seen Keaton’s entire catalog, The Great Buster does have a few insights and observations worth seeking out.

—Michael R. Neno, 2020 September 14