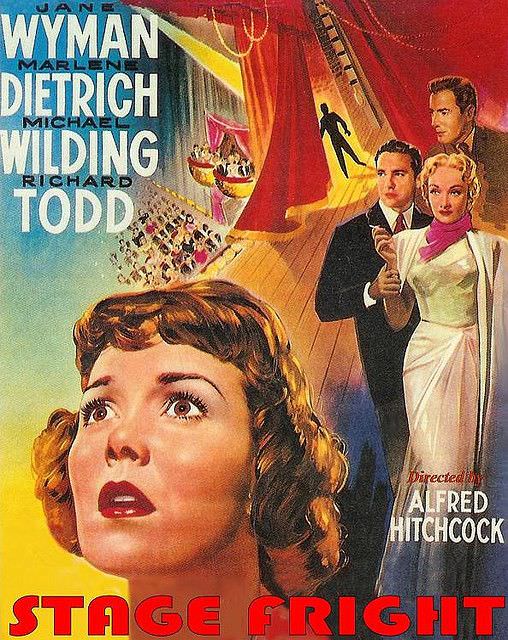

Stage Fright

Filmed, along with Under Capricorn, between the masterpieces Rope (1948) and Strangers on a Train (1952), Stage Fright is a low-key, almost intentionally casual, minor thriller. Alfred Hitchcock’s daughter, Patricia, was attending the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London at the time of the shooting and had a small role in Stage Fright. The script for the film was changed from Selwyn Jepson’s novel to feature another Royal Academy of Dramatic Art student, Eve Gill (Jane Wyman). Moreover, the screenplay is credited to Alma Reville, Alfred’s wife. Made on a trip to London, the film is a family endeavor all around.

Filmed, along with Under Capricorn, between the masterpieces Rope (1948) and Strangers on a Train (1952), Stage Fright is a low-key, almost intentionally casual, minor thriller. Alfred Hitchcock’s daughter, Patricia, was attending the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London at the time of the shooting and had a small role in Stage Fright. The script for the film was changed from Selwyn Jepson’s novel to feature another Royal Academy of Dramatic Art student, Eve Gill (Jane Wyman). Moreover, the screenplay is credited to Alma Reville, Alfred’s wife. Made on a trip to London, the film is a family endeavor all around.

Stage Fright begins with a thrill as Eve Gill is in the process of helping her romantic interest, Jonathan (Richard Todd), escape from the police, wanted for murder. He tells her the story of how he aided stage singer Charlotte Inwood (Marlene Dietrich) after she killed her husband, helping her hide her blood-stained dress. Jonathan stupidly (he’s infatuated with Inwood), returns to her apartment to retrieve clean clothes for her, but is seen by Inwood’s maid, Nellie Goode (Kay Walsh).

Wanting to help her friend, Eve takes Jonathan to hide in the sea-side house of her father, Commodore Gill (Alastair Sim). Realizing that she needs to get closer to the situation to find evidence which will prove Jonathan’s innocence, Eve’s acting skills are put to the test. She first poses as a depressed melancholic to gain the sympathy of detective Wilfred Smith (Michael Wilding), also investigating the case. She then poses as a reporter to get information from Nellie Goode, talking her into introducing Eve as Nellie’s cousin in order to get a gig as Inwood’s maid. An actress acting as a reporter who’s acting as a maid to another actress is just the beginning of a series of ever more complex delusions.

She then poses as a reporter to get information from Nellie Goode, talking her into introducing Eve as Nellie’s cousin in order to get a gig as Inwood’s maid. An actress acting as a reporter who’s acting as a maid to another actress is just the beginning of a series of ever more complex delusions.

The deceitfulness doesn’t stop with Eve. Commodore Gill lies to Eve’s mother and Wilfred Smith to hide Jonathan. Inwood has her own self-serving lies. And Jonathan, who never seemed stable and likable to begin with (begging the question of why Eve would go to such lengths to help him), eventually reveals duplicitous machinations of his own, ones which put into question everything we know about the police case.

As with so many Hitchcock films, the screenplay is constructed to lead up to key cinematic set-pieces (the crop duster sequence in North by Northwest being a prime example). Stage Fright‘s most memorable may be the very rainy RADA garden party, a small movie all its own, wherein many of the film’s characters and agendas crisscross and collide (comedian Joyce Grenfell’s entreaties to “shoot lovely ducks” for charity are hilarious).

Marlene Dietrich, whose role was rewritten once she was hired to emphasize her public persona, is given a musical number, Cole Porter’s “The Laziest Gal in Town,” sung, choreographed, and directed with consummate Hollywood glamour. Similar glamour eluded Jane Wyman; I was disappointed to read in the Hitchcock/Truffaut interview book that Wyman cried when watching the rushes of herself playing a dowdy maid to the sultry Dietrich (as if Wyman’s maid costume could have hidden her beauty). Stage Fright was a suspense movie, not a beauty contest; besides, as Hitchcock was known to say: “It’s only a movie.”

Stage Fright is fine—if relatively unambitious—entertainment and a good reminder that even minor Hitchcock is worth watching, if only a couple times throughout your years.

—Michael R. Neno, 2020 Sep 23