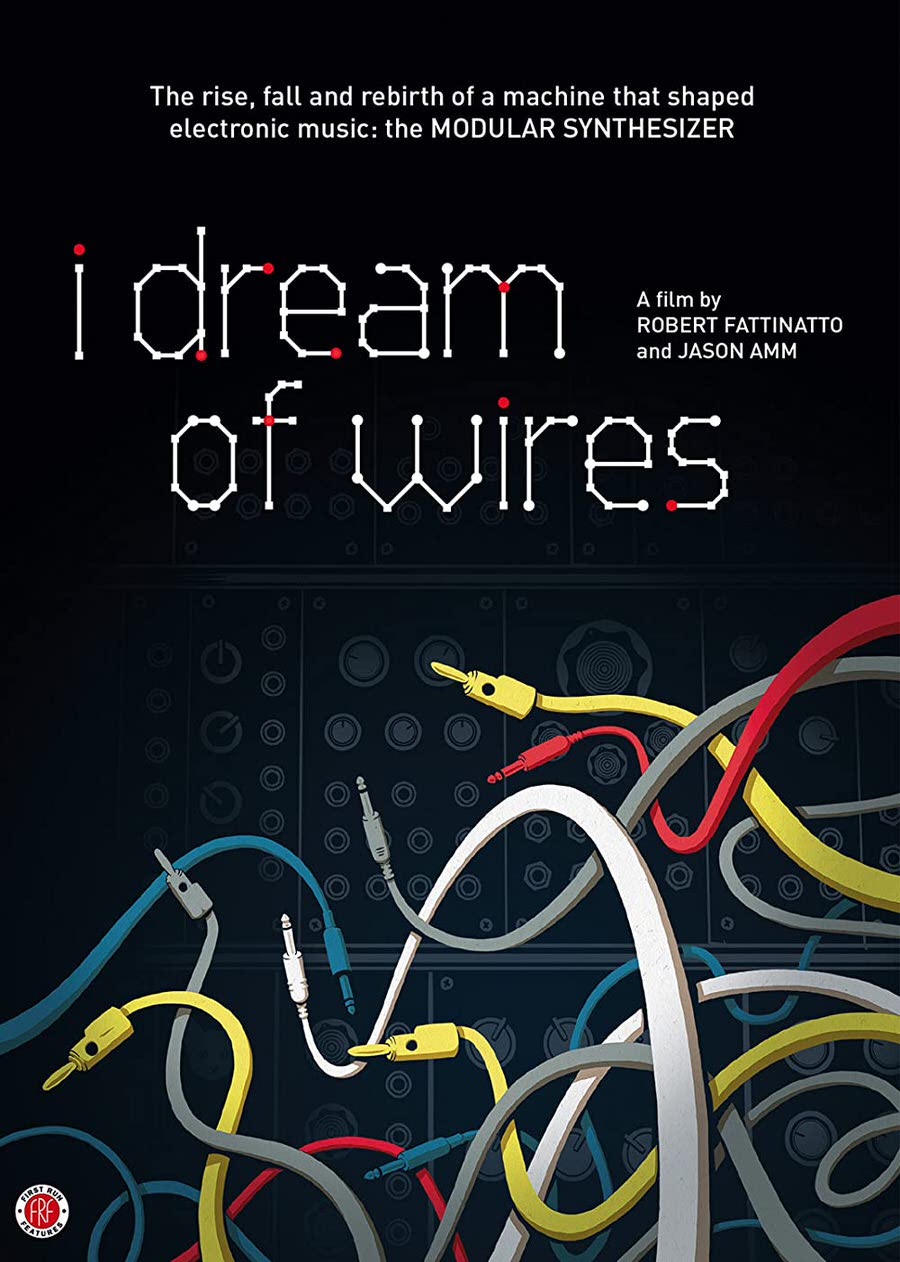

I Dream of Wires

Directed by Robert Fattinatto and Jason Amm (2014) ***

Few technologists in the early ’90s, when the internet was being birthed and the future looked like a science fiction dream, could have predicted that a substantial portion of a new generation would rebel against the digital realm and embrace, instead, technologies considered at the time deservedly dead — though the undercurrents emanating from a new literary and visual genre eventually called Steampunk indicated where things were going. At a time when most were selling, giving or throwing away their vinyl records for new, shiny, “perfect” compact discs, few could have imagined the new technology would be  abandoned so soon, nor that vinyl would again outsell it, as it does now. CDs, it eventually turned out, became something your parents listened to, the most uncool format imaginable (besides 8-tracks). As detailed in the mostly astute book The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter, by David Sax, the tactile, the socially interactive, the anti-digital is what’s meaningful to many young people bored or contemptuous of aspects of the modern world. That a similar revival is happening to an instrument, the modular synthesizer, that for decades was derided as cold, unfeeling and not quite “real” is a little ironic — but still understandable. The classic synthesizer is a model of tactility. It requires the continuous input and interchanging of patch cables in order to produce the music a player envisions — or, through this unique mechanism, discovers.

abandoned so soon, nor that vinyl would again outsell it, as it does now. CDs, it eventually turned out, became something your parents listened to, the most uncool format imaginable (besides 8-tracks). As detailed in the mostly astute book The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter, by David Sax, the tactile, the socially interactive, the anti-digital is what’s meaningful to many young people bored or contemptuous of aspects of the modern world. That a similar revival is happening to an instrument, the modular synthesizer, that for decades was derided as cold, unfeeling and not quite “real” is a little ironic — but still understandable. The classic synthesizer is a model of tactility. It requires the continuous input and interchanging of patch cables in order to produce the music a player envisions — or, through this unique mechanism, discovers.

Robert Fattinatto and Jason Amm’s addictive documentary on the rise, fall and resurgence of this distinctive instrument is not just for music lovers or musicians. It’s an inspiring tale of stubborn ingenuity. The instruments’ creators and users were initially all societal outsiders, fringe eccentrics who experimented with new sounds and ways of creating and listening, sometimes at great odds, and with no guarantee of success.

The first modular synthesizer was invented by the German engineer Harold Bode, who could himself be the subject of a documentary, so varied and fascinating are his many inventions. Bode’s ideas were soon picked up and experimented on in the 1960s by two concurrent but markedly different Americans: Robert Moog, on the east coast, and Don Buchla on the west coast.

The first modular synthesizer was invented by the German engineer Harold Bode, who could himself be the subject of a documentary, so varied and fascinating are his many inventions. Bode’s ideas were soon picked up and experimented on in the 1960s by two concurrent but markedly different Americans: Robert Moog, on the east coast, and Don Buchla on the west coast.

Moog, who built his first theremin at the age of fourteen, started his own mail order theremin business. In 1964, Moog introduced the first commercial synthesizer, composed of patch cord-connected modules and playable via a keyboard. Most early users of his device were classical and avant-garde composers, though it would eventually be used by rock artists. Don Buchla’s more unwieldy and deliberately noncommercial Buchla 100 series Modular Electronic Music System was developed at and for the San Francisco Tape Music Center, a workplace for a collective of experimental musicians, including minimalists Terry Riley and Steve Reich. Composer Morton Subotnick was instrumental in the funding and production of the new technology, used in his groundbreaking 1967 work, Silver Apples of the Moon.

When then-Walter Carlos released Switched-On Bach in 1968, played on a Moog synthesizer, it made the instrument both successful and desirable, and went on to become the second classical record in history to sell over a million copies. The unique, deep and rich sounds generated by modular synthesizers (especially when experienced live) were eventually superseded by new, competing instruments such as the Prophet-5 and Fairlight CMI, sought after due to their easy use. The Fairlight offered the ability to record and play back sequences, negating the necessity to patch cords into modules. These newer instruments, with pre-packaged sounds and their limitations on experimentation, gave recordings at the time a similar sound, a glossy sheen that was new then, but since become cringingly dated.

When then-Walter Carlos released Switched-On Bach in 1968, played on a Moog synthesizer, it made the instrument both successful and desirable, and went on to become the second classical record in history to sell over a million copies. The unique, deep and rich sounds generated by modular synthesizers (especially when experienced live) were eventually superseded by new, competing instruments such as the Prophet-5 and Fairlight CMI, sought after due to their easy use. The Fairlight offered the ability to record and play back sequences, negating the necessity to patch cords into modules. These newer instruments, with pre-packaged sounds and their limitations on experimentation, gave recordings at the time a similar sound, a glossy sheen that was new then, but since become cringingly dated.

Fattinatto and Amm feature interviews, new and archival, with nearly all the key players: Moog, Don Buchla, Subotnick, and several post-punk musicians who fell in love with the modular synthesizer and took it into new realms, such as Gary Numan, Vince Clarke (Erasure), Chris Carter (Throbbing Gristle) and Trent Rezner (Nine Inch Nails). (It was also nice to see the criminally obscure Ohio composer and

experimentalist Jon Sonnenberg.)

I Dream of Wires is  strong in its representation of the resurgence of the modular synthesizer, as young musicians and builders, eager to play around with something other than invisible digital zeroes and ones, have embraced the old. Like typewriters, physical books, board games and other analog products, the synthesizer is now supported by a network of small manufacturing companies, enthusiasts, conventions and touring EDM bands. The music for the film was composed by Amm, under the guise of his stage name, Solvent, a proponent of IDM (or, Intelligent Dance Music, a more cerebral, less dancable version of EDM). For those who want more — much more — there is a four-hour version of this film available: I Dream of Wires, Hardcore Edition.

strong in its representation of the resurgence of the modular synthesizer, as young musicians and builders, eager to play around with something other than invisible digital zeroes and ones, have embraced the old. Like typewriters, physical books, board games and other analog products, the synthesizer is now supported by a network of small manufacturing companies, enthusiasts, conventions and touring EDM bands. The music for the film was composed by Amm, under the guise of his stage name, Solvent, a proponent of IDM (or, Intelligent Dance Music, a more cerebral, less dancable version of EDM). For those who want more — much more — there is a four-hour version of this film available: I Dream of Wires, Hardcore Edition.

This 96-minute edition, available on DVD from First Run Features, does include as supplementary material the instructional short Modular Synth 101, a tour of Vince Clarke’s studio, an extended interview with Trent Reznor and much more modular material.

—Michael R. Neno, 2022 Mar 22