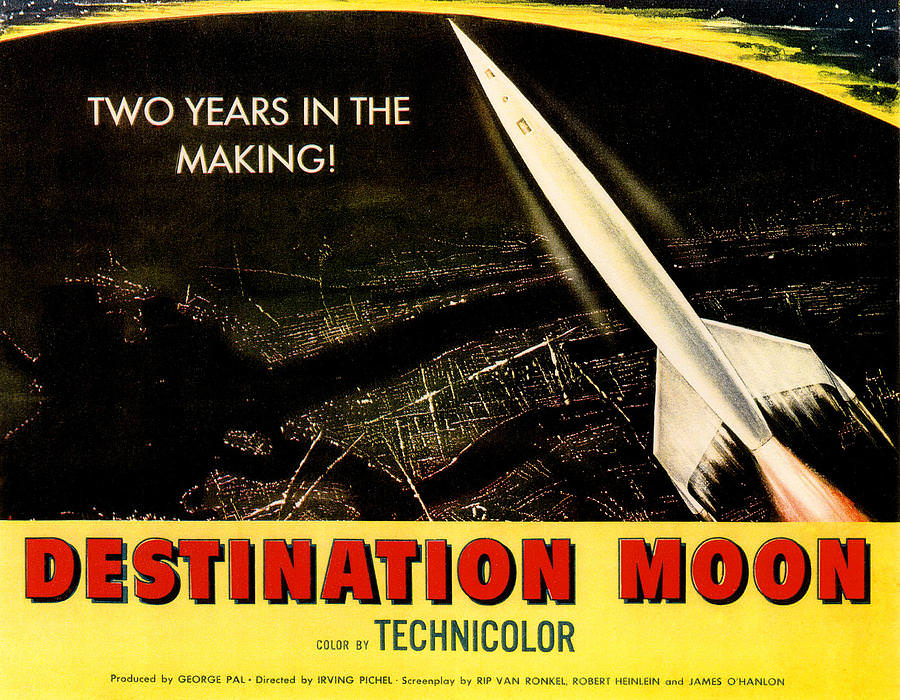

Destination Moon

Directed by Irving Pichel (1950) **1/2

In the history of science fiction films, Irving Pichel’s Destination Moon is a kind of missing link between the fanciful space opera serials of Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers and the “hard” science fiction of later ’60s and ’70s films like 2001: A Space Odyssey and Silent Running. Though it seems dated and naive now, it was the first science fiction film to present the scientific means by which a real manned trip to the moon might be feasible. It, moreover, predicts that manned trips will be funded by independent industries due to incapability or disinterest on the part of the U.S. government.

In the history of science fiction films, Irving Pichel’s Destination Moon is a kind of missing link between the fanciful space opera serials of Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers and the “hard” science fiction of later ’60s and ’70s films like 2001: A Space Odyssey and Silent Running. Though it seems dated and naive now, it was the first science fiction film to present the scientific means by which a real manned trip to the moon might be feasible. It, moreover, predicts that manned trips will be funded by independent industries due to incapability or disinterest on the part of the U.S. government.

Though directed by the longtime actor/director Irving Pichel, Destination Moon was producer George Pal’s project from the beginning (Pal is best known today for his later films, The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds). Destination was part of a two-picture deal Pal made with the independent film production company, Eagle-Lion Films. In a bid for scientific accuracy, Pal hired author Robert A. Heinlein to contribute to the script and hired astronomical artist Chesley Bonestell to design and paint backdrops. The relatively serious tone of the film, at odds with Saturday afternoon matinee material, was conveyed and promoted in numerous slick magazines and newspapers well before the film’s release, with Bonestell’s paintings a big selling point for the picture (as no one, including Bonestell, knew exactly what the surface of the moon would be like). Pal also drew upon the expertise of astronautics and rocketry expert Hermann Oberth.

The least interesting aspect of Destination is its nearly interchangeable characters (and actors), whose only function is to make sure the U.S. gets to the moon first. When a rocket test fails, General Thayer (Tom Powers) and scientist Charles Cargraves (Warner Anderson) are suspicious it was foreign sabotage. Determined that the U.S. must get to the moon first (the first nation to reach the moon can use it to attack the Earth), they and aircraft industrialist Jim Barnes (John Archer), make a presentation to a roomful of well-heeled power brokers, using a Woody Woodpecker cartoon to demonstrate the basic scientific principals by which a rocket could leave the Earth’s atmosphere and safely land on (and return from) the moon. Convinced, the project is initiated, all outside the scope of the government. Two unforeseen events nearly derail the launch: one crew member falls ill and is replaced by Joe Sweeney (Dick Wesson in an unfunny comedy relief role). Local authorities, concerned about a possible radiation leak, also try to prevent the launch, but are minutes too late.

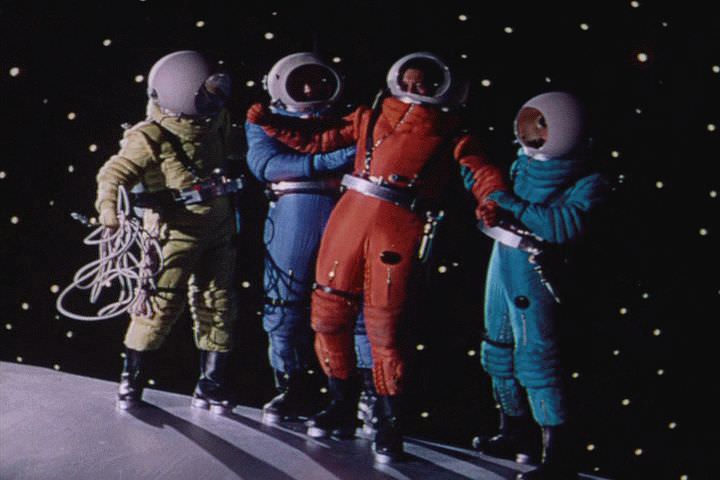

It’s amazing how much influence Destination Moon had on later popular culture (and, quite likely, on the public’s understanding, acceptance and enthusiasm for U.S. space travel). The quick and illegal shooting off into space with four cosmonauts is echoed in the origin of The Fantastic Four in their first issue (1961). 2001: A Space Odyssey, like Destination,  has no romantic subplot (a rarity in films of both the ’50s and ’60s). Like Destination, 2001 uses a broken antenna as a reason for his astronauts to leave the safety of their ship, both films showing characters adrift in space. 2001‘s costume design also echoes Destination‘s color-coded spacesuits. It’s worth noting that 2001 was co-written by Arthur C. Clarke — like Heinlein, another “hard” science fiction author of the genre’s golden age.

has no romantic subplot (a rarity in films of both the ’50s and ’60s). Like Destination, 2001 uses a broken antenna as a reason for his astronauts to leave the safety of their ship, both films showing characters adrift in space. 2001‘s costume design also echoes Destination‘s color-coded spacesuits. It’s worth noting that 2001 was co-written by Arthur C. Clarke — like Heinlein, another “hard” science fiction author of the genre’s golden age.

George Pal’s experience in hand puppets (popularized in his earlier Puppetoons series) is used throughout the film (as is what looks like Claymation for some long shots); midgets were even used in scenes calling for forced perspective. Destination was made in bright, vivid Technicolor and won an Academy award for special effects.

Destination Moon‘s shoved-in comedy relief and naivete concerning the politics of a space launch on a scale shown here badly date the film. It’s also true, though, that films like 2001: A Space Odyssey, and perhaps the actual manned moon landing itself (both only a year apart) were no doubt inspired by and a response to the achievements the film predicts. It isn’t a great film but is an important one.

—Michael R. Neno, 2021 February 2